I've seen a few studies come across my desk that predict the economic effects of global warming on olive oil-producing regions in an attempt to declare the winners and losers of climate change.

At the same time, we're getting inquiries through our OOT editorial support line from journalists at popular news outlets who are asking us who the victims and victors will be when the earth gets a little warmer than it is now.

The questions we get would be shocking if they weren't so morose: "Who will be the winners of climate change in the olive oil industry?" It's almost like asking who might survive a nuclear war.

In light of all of the interest in climate change winners and losers, it wouldn't surprise me if Las Vegas had some kind of pool going: "I'll put $5,000 on Morocco at +2°C."

I can understand the cynicism after the previous U.S. leadership pulled out of the Paris Agreement and offered little hope to those of us who share the conviction that global warming is a disaster that can still be avoided.

Maybe that was when some researchers pivoted from finding new ways to combat the trend to predicting its inevitable effects and journalists threw in the towel in headlines with the wording of sports scores.

Russia was supposed to be a winner. Vladimir Putin even went so far as to say that if the planet warmed by a few degrees, "it wouldn't be so bad."

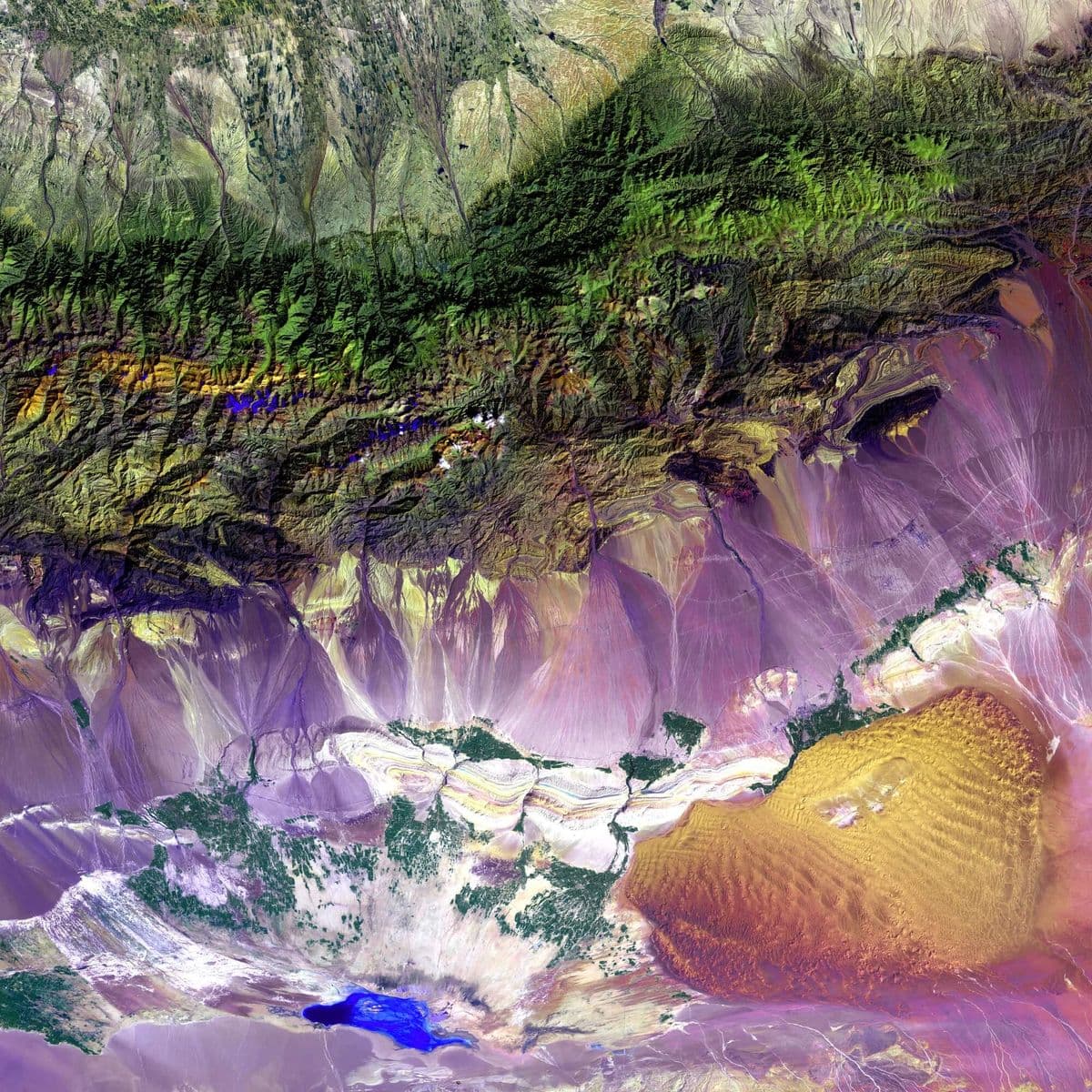

But there are hidden perils that are endlessly complex and impossible to predict. In Russia, climate change was blamed for a peat fire measuring 140,000 sq. km – about the size of the U.S. state of Montana. Coined "zombie fires" by locals, the smoldering earth released record amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere to add insult to injury.

We won't be celebrating any winners among our olive oil-producing regions if the climate projections become a reality. In the end, we will all lose.

Organic defenses against pests that thrive in warmer temperatures will lose. More farms will abandon environmentally-friendlier approaches in favor of chemical pesticides.

As certain regions become less hospitable to olives, farmers will choose other crops resulting in the gradual extinction of local autochthonous olive varieties. We will be losing the range of terroirs that provide extra virgin olive oils with complexity and distinction.

When production is no longer viable in places it has flourished for hundreds, or even thousands, of years, it will chip away at one of the cultural cornerstones of our civilization.

When small, family farms in traditional producing regions are replaced by more efficient and industrial startups, products will be more homogeneous.

Fewer cultivars will be chosen for the new, modern harvesting operations. There will be fewer brands, but you'll be able to buy a bland, nameless, soulless liter for $4.99.

Of course, it wouldn't be the first time an artisanal product is replaced by industrial manufacturing and family farms succumb to multinationals. Check the provenance of the butter or chicken in your fridge.

Just don't ask who the winners among us will be.

In Las Vegas, it's called a "lay bet" when you wager that one side will not win a contest. In the global warming game, the smart money is a lay bet.

Climate change is a bad hand for everyone in our industry. In the end, we all lose.